Harry George Hawker (1889 - 1921)

Harry Hawker was one of the worlds pioneering aviators. In 1913 he set an endurance record of 8 hours and 20 minutes, set a new height record of 11,700 feet and then later an air speed record of 92 miles per hour. Hawker also supposedly solved the problem of the spin. Until 1914 a spin was terminal, a pilot generally surviving on luck, Hawker surmised that the counter-intuitive action of pushing the stick forward would solve the problem. He was correct. Hawker was chief test pilot and designer for Sopwith, one of the leading aircraft manufacturers of the day.

After WWI, Sopwith went out of business and Hawker started the H.G. Hawker Engineering which would later produce military designs such as the Hawker Fury, Hawker Hurricane and in more modern times the Hawker-Siddely Harrier. Harry Hawker died in 1921 in an air accident.

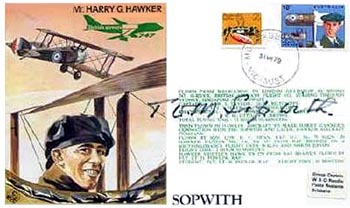

Hawker and Grieve The second plane to attempt the non-stop crossing of the Atlantic Ocean and the first to fly from west to east in the great race, was the team of Hawker and Grieve. These First World War veterans flew a Sopwith plane, aptly called the Atlantic. It was a land-based biplane of some 350 horsepower. Part of their plane formed a boat that could be detached in case they had trouble over the ocean. This team took off from a field in Mount Pearl on May 18, 1919, and shortly thereafter, Hawker jettisoned the undercarriage. The wheels were later recovered by local fishermen and are in the Newfoundland Museum in St. John's. After several hours into the flight, problems began to happen with the wireless, and later, overheating problems with the engine forced them to ditch in the Atlantic some 14.5 hours into the flight. They abandoned their plane and were rescued by the Danish ship SS Mary. Since the Danish ship carried no wireless, their safe rescue could not be reported and no wreckage was found. There was great joy a week later on the 25th of May, when word was received that the crew of the Atlantic were picked up by the SS Mary. The British destroyer Woolston came to the Danish ship and took the aviators off and brought them to Scapa Flow where they spent the night on the HMS Revenge. It is recorded that the King of England gave the aviators the Air Force Cross, and the Daily Mail gave them a consolation prize of 5000 pounds.

Hawker and Grieve's Sopwith Atlantic

Sopwith Atlantic http://www.airforce.dnd.ca The first flight in Newfoundland was made by Harry George Hawker and Kenneth Mackenzie-Grieve in a Sopwith Atlantic on the occassion of its first Newfoundland test flight on 10 April, 1919. Subsequently, on 18 May 1919, the first attempt at a direct trans-Atlantic flight by a heavier-than-air machine was made by these same men in the same Aircraft from St. John's, Newfoundland, only to see them forced down in the ocean and rescued. Sopwith designed this machine for commercial transport, especially the trans-Atlantic type, and named it the "Sopwith Transport (Trans-Atlantic Type)". It was a two seater with a cargo capacity (including 330 gallons of fuel) of about 3,000 pounds, and an in-flight endurance of 22 hours at 100 mph, quite a distinct departure from the single seat fighter type Aircraft with which the firm had hitherto been concerned.

1889 : Harold George Hawker is born at Moorabbin in Victoria, Australia, 22 January 1901-04 : Hawker works as a trainee mechanic at the Melbourne branch of Hall & Warden bicycle depot

1907-11 : Runs his own car servicing workshop at Caramut in western Victoria and also during this time (1908) was a member, along with his brother (Herbert Stanley Hawker), of the St. Kilda Brass Band 1911-12 : Works for the Commer Car Company, England 1911 and the Mercedes and Austro-Daimler Companies, 1912 1912 : Joins the Sopwith Aviation Company working on the Sopwith-Wright biplane 1912 1912-c.1918 : Senior test pilot and designer for Sopwith Aviation Company 1913 : Wins £1,000 prize for the first flight of 1,000 miles on an outward course. Designs the Sopwith Tabloid 1914 : Ships the Tabloid to Australia and gives practical flying exhibitions carrying many notable citizens as passengers 1919 : Enters a number of speedboat and motor racing events. Wins £5,000 for the first pilot to fly over 1,000 miles of water without touching down 1920 : Forms the H.G. Hawker Engineering Company. Drives the first car to reach 100 miles an hour 1921 : Dies in an air crash at Hendon, England, 12 July

Harry Hawker: The Boy who wanted to Fly Harry George Hawker, the second son of a Moorabbin blacksmith of Cornish blood was born in a small rented terrace cottage in Wickham Rd., on January 22, 1889. When he was born, John King and his wife Deborah, the original settlers of the Moorabbin district were still living on the land which they had pioneered as the first white settlers to take up residence. Australia itself had only been established 101 years and already there was a new era which in turn heralded a crisp challenge to a coming generation to face up to the machine age. Harry Hawker although still a schoolboy was ever eager to accept that challenge so much so in fact that he disregarded the essential pre-requisite of a sound primary education. His first tuition was gained at the Worthing Road State School, Moorabbin, but the depression coupled with his own lack of interest in basic education saw him move to another three schools in the six short years of learning that represented the only schooling he was ever to enjoy. The fourth and final school that he attended was at Brighton and it was from here that this lad with the great mechanical mind finally decided to abscond from school for all time to accept five shillings per week from the motor firm of Hall and Wardens at a time when the adult wage had reached an all time high at six shillings per day. But to Hawker a paid job in the field of mechanical engineering was all that mattered....more

Harry Hawker

The history of Harry George Hawker has been told with competence and affection by his wife, Muriel nee Peaty, in H.G. Hawker, Airman: His Life and work, published in 1922 in London.  Harry George Hawker was born in South Brighton (Moorabbin) on 22 January 1889 and began work at the age of twelve years with a firm of bicycle and motor agents. Three years later he joined the notable Tarrant Motor Company and became a competent motor mechanic and driver with an incipient interest in aeroplanes.

Harry George Hawker was born in South Brighton (Moorabbin) on 22 January 1889 and began work at the age of twelve years with a firm of bicycle and motor agents. Three years later he joined the notable Tarrant Motor Company and became a competent motor mechanic and driver with an incipient interest in aeroplanes.About 1908 he became chauffeur and mechanic for Ernest de Little, pastoralist of 'Caramut House' in the western district, and remained there until April 1911 when he went to England with a friend having similar interests.

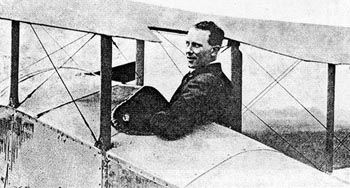

On his arrival in London he found work with three motor firms in turn and in June 1912 secured more rewarding and promising work with Sopwith Aviation Company. There he began a brilliant career as flier and engineer, a career which was to be dramatically short. Harry Hawker, Sopwith 3-Seater, c.1913

Harry Hawker, Australia, 1914

Harry Hawker

Early in 1914 he bought a biplane to Australia and gave demonstration flights from racecourses in Melbourne and Sydney. He returned to England and, on the outbreak of war in august 1914, became test-pilot for military aircraft and his skill as an engineer influenced designs. At the end of the war he returned to civil aviation and took an important part in the design and construction of a special aircraft for crossing the Atlantic from Newfoundland to Ireland. He began the flight on 18 May 1919 with Lieutenant-Commander Mackenzie-Grieve as navigator but they were forced into the sea by radiator failure. Fortunately they came down in sight of a Danish steamer and were rescued despite rough sea. The vessel was without radio facilities and news of their safety had to await arrival at a Scottish port six days later. The fliers were taken to Scapa Flow where the Navy welcomed them with great enthusiasm and sent them to London by train. At every station along the way they were greeted by large crowds of cheering people and on arrival in London were given a massive demonstration. An Australian military band and an escort of Australian soldiers. Congratulatory messages poured in from all parts of the civilized world, that from Australia by its Prime Minister. The King received them at Buckingham Palace and they were given the Air Force Cross ordinarily reserved for service men only. As the call for aircraft fell off after the war, the Sopwith Company turned to other products and Harry became involved in motor car racing and getting more power out of internal combustion engines. The H.G. Hawker Engineering Company was formed to manufacture motor-cycle and light-weight vehicle bodies of aluminium. He continued his interest in aeroplanes but on the 16 July 1921, whilst testing a biplane for entry in an Aerial derby, was killed instantly when the plane crashed for some reason unknown.

His death caused world-wide sorrow and tributes poured in. Perhaps the following was typical: "Harry Hawker was stamped with genuineness. he was a simple, clean, straight-souled man. He was bred and born to do things. he did them: he did them thoroughly, deep-bitten. He made and left his mark. but on all that he did he worked so simply, so single-mindedly, that in his passing the world of actualities loses not merely a fine airman and a cunning handler of motor-cars".The City of Moorabbin remembers him as 'Pioneer of high and long distance flying' in a worthy memorial in its airport.

Harry George Hawker was born in 1889 at Moorabbin, Victoria, the son of an engineer and wheelwright. His father had an engineering interest and designed and built various steam engines, and a steam powered automobile. The enthusiasm influenced Harry, and on leaving school he found work with a company manufacturing bicycles, before becoming a chauffer and mechanic.

Within a few weeks he had persuaded the founder, Tom Sopwith, to teach him to fly. Four days after his first lesson he was capable of flying a 50 minute solo, and after a month he had his "Aviator's Certificate". At the age of 20, Harry Hawker was put in charge of Sopwith's hangars and of competition, demonstration and test flying. ...more

The Mastery of The Air

Aeroplanes and Airmen : Three Historic Fights When the complete history of aviation comes to be written, there will be three epoch-making events which will doubtless be duly appreciated by the historian, and which may well be described as landmarks in the history of flight. These are the three great contests organized by the proprietors of the Daily Mail, respectively known as the London to Manchester flight, the Round Britain flight in an aeroplane, and the Water-plane flight round Great Britain. The third historic flight was made by Mr. Harry Hawker, in August, 1913. This was an attempt to win a prize of L5000 offered by the proprietors of the Daily Mail for a flight round the British coasts. The route was from Cowes, in the Isle of Wight, along the southern and eastern coasts to Aberdeen and Cromarty, thence through the Caledonian Canal to Oban, then on to Dublin, thence to Falmouth, and along the south coast to Southampton Water. Two important conditions of the contest were that the flight was to be made in an all-British aeroplane, fitted with a British engine. Hitherto our aeroplane constructors and engine companies were behind their rivals across the Channel in the building of air-craft and aerial engines, and this country freely acknowledged the merits and enterprise of French aviators. Though in the European War it was afterwards proved that the British airman and constructor were the equals if not the superiors of any in the world, at the date of this contest they were behind in many respects. As these conditions precluded the use of the famous Gnome engine, which had won so many contests, and indeed the employment of any engine made abroad, the competitors were reduced to two aviation firms; and as one or these ultimately withdrew from the contest the Sopwith Aviation Company of Kingston-on-Thames and Brooklands entered a machine.

Harry Hawker FDC signed by Tom Sopwith

Thomas Sopwith chose for his pilot a young Australian airman, Mr. Harry Hawker. This skilful airman came with three other Australians to this country to seek his fortune about three years before. He was passionately devoted to mechanics, and, though he had had no opportunity of flying in his native country, he had been intensely interested in the progress of aviation in France and Britain, and the four friends set out on their long journey to seek work in aeroplane factories. All four succeeded, but by far the most successful was Harry Hawker. Early in 1913 Mr. Sopwith was looking out for a pilot, and he engaged Hawker, whom he had seen during some good flying at Brooklands. In a month or two he was engaged in record breaking, and in June, 1913, he tried to set up a new British height record. In his first attempt he rose to 11,300 feet; but as the carburettor of the engine froze, and as the pilot himself was in grave danger of frost-bite, he descended. About a fortnight later he rose 12,300 feet above sea-level, and shortly afterwards he performed an even more difficult test, by climbing with three passengers to an altitude of 8500 feet. With such achievements to his name it was not in the least surprising that Mr. Sopwith's choice of a pilot for the water-plane race rested on Hawker. His first attempt was made on 16th August, when he flew from Southampton Water to Yarmouth--a distance of about 240 miles--in 240 minutes. The writer, who was spending a holiday at Lowestoft, watched Mr. Hawker go by, and his machine was plainly visible to an enormous crowd which had lined the beach. To everyone's regret the pilot was affected with a slight sunstroke when he reached Yarmouth, and another Australian airman, Mr. Sidney Pickles, was summoned to take his place. This was quite within the rules of the contest, the object of which was to test the merits of a British machine and engine rather than the endurance and skill of a particular pilot. During the night a strong wind arose, and next morning, when Mr. Pickles attempted to resume the flight, the sea was too rough for a start to be made, and the water-plane was beached at Gorleston. Mr. Hawker quickly recovered from his indisposition, and on Monday, 25th August, he, with a mechanic as passenger, left Cowes about five o'clock in the morning in his second attempt to make a circuit of Britain. The first control was at Ramsgate, and here he had to descend in order to fulfil the conditions of the contest. Ramsgate was left at 9.8, and Yarmouth, the next control, was reached at 10.38. So far the engine, built by Mr. Green, had worked perfectly. About an hour was spent at Yarmouth, and then the machine was en route to Scarborough. Haze compelled the pilot to keep close in to the coast, so that he should not miss the way, and a choppy breeze some what retarded the progress of the machine along the east coast. About 2.40 the pilot brought his machine to earth, or rather to water, at Scarborough, where he stayed for nearly two hours. Mr. Hawker's intention was to reach Aberdeen, if possible, before nightfall, but at Seaham he had to descend for water, as the engine was becoming uncomfortably hot, and the radiator supply of water was rapidly diminishing. This lost much valuable time, as over an hour was spent here, and it had begun to grow dark before the journey was recommenced. About an hour after resuming his journey he decided to plane down at the fishing village of Beadwell, some 20 miles south of Berwick. At 8.5 on Tuesday morning the pilot was on his way to Aberdeen, but he had to descend and stay at Montrose for about half an hour, and Aberdeen was reached about 11 a.m. His Scottish admirers, consisting of quite 40,000 people at Aberdeen alone, gave him a most hearty welcome, and sped him on his way about noon. Some two hours later Cromarty was reached. Now commenced the most difficult part of the course. The Caledonian Canal runs among lofty mountains, and the numerous air-eddies and swift air-streams rushing through the mountain passes tossed the frail craft to and fro, and at times threatened to wreck it altogether. On some occasions the aeroplane was tossed up over 1000 feet at one blow; at other times it was driven sideways almost on to the hills. From Cromarty to Oban the journey was only about 96 miles, but it took nearly three hours to fly between these places. This slow progress seriously jeopardized the pilot's chances of completing the course in the allotted time, for it was his intention to make the coast of Ireland by nightfall. But as it was late when Oban was reached he decided to spend the night there. Early the following morning he left for Dublin, 222 miles away. Soon a float was found to be waterlogged and much valuable time was, spent in bailing it dry. Then a descent had to be made at Kiells, in Argyllshire, because a valve had gone wrong. Another landing was made at Larne, to take aboard petrol. As soon as the petrol tanks were filled and the machine had been overhauled the pilot got on his way for Dublin. For over two hours he flew steadily down the Irish coast, and then occurred one of those slight accidents, quite insignificant in themselves, but terribly disastrous in their results. Mr. Hawker's boots were rubber soled and his foot slipped off the rudder bar, so that the machine got out of control and fell into the sea at Lough Shinny, about 15 miles north of Dublin. At the time of the accident the pilot was about 50 feet above the water, which in this part of the Lough is very shallow. The machine was completely wrecked, and Mr. Hawker's mechanic was badly cut about the head and neck, besides having his arm broken. Mr. Hawker himself escaped injury. All Britons deeply sympathized with his misfortune, and much enthusiasm, was aroused when the proprietors of the Daily Mail presented the skilful and courageous pilot with a cheque for L1000 as a consolation gift.

Hawker Pacific Aerospace Hawker Pacific Aerospace's history began in 1912 with Harry Hawker asking Thomas Sopwith for flying lessons. Within a few years Hawker became one of the best pilots of his time. He was Sopwith's top test pilot. After World War I the government canceled all orders with Sopwith leaving him in financial ruins. Hawker and a group of people took over all of Sopwith's patent rights, forming Hawker Engineering. In 1921 Harry Hawker died from injuries obtained from a airplane crash. After Hawker's death Thomas Sopwith became Chairman of Hawker Engineering. Within a short time Hawker Engineering had taken over many other companies related to Aviation. In 1933, Hawker Engineering became Hawker Aircraft Ltd., and shortly after that became Hawker Siddeley Company. In 1934, Hawker Aircraft was given the contract to build an aircraft for the RAF. This aircraft became one England's strongest weapons against Germany, the Hurricane. Hawker Siddeley went on to produce many other aircraft for the war effort. In 1967, Hawker Siddeley produced an aircraft, which was in great demand and interest throughout the world. It revolutionized the combat aircraft role of both helicopters and jet fighters-the Hawker Harrier. Although the Hawker Siddeley name remains, the aviation section was absorbed by British Aerospace Corp. in 1977. Hawker Pacific was formed in 1980. In 1991, Hawker Siddeley was absorbed by BTR Aerospace Group. In 1994, Hawker Pacific Inc. merged with Dunlop Aviation Inc and in 1996, Hawker Pacific was sold by BTR and became a stand-alone company. In 1998, Hawker Pacific completed its initial public offering of common stock and used the proceeds to acquire the landing gear, flap track and flap carriage operation from British Airways. Today, Hawker Pacific Aerospace has nearly 500 employees in Los Angeles, London, and Amsterdam and is one of the world's leading providers of aircraft landing gear maintenance service.

Harry Hawker (1889 - 1921) Another famous Australian aviator was Harry Hawker, a test pilot with the Sopwith aviation company. Renowned as a fearless and daring pilot, he was perhaps the most famous aviator of the time. Born at Moorabbin, near Melbourne, he trained as a motor mechanic, then went to England and began flying with Sopwith Aviation in June 1912. In October 1913 he set a British endurance record of 8 hours and 23 minutes, which stood for several years. On 31st May 1913, he set an altitude record of 11,450 feet. In early 1914, a Frenchman, Pegoud, had looped an aircraft for the first time. Then, on June 17th, at the famous Brooklands racetrack in England, pilots, mechanics and enthusiasts watched in awe as young Australian Harry Hawker looped-the-loop in a Sopwith Scout twelve times in succession. During WW1, he tested 295 aircraft and helped improve their performance and safety.

Harry Hawker's Sopwith Bat Boat

"The new Sopwith Bat-Boat Flying Machine, at Cowes, British built, throughout, fitted with wheels to enable it to descend upon the land. Winner of the 500 pound Mortimer-Singer prize 1913, successfully piloted by Mr. Harry Hawker, who is seated on the boat, and is also the Holder of the British Altitude record of 1913."In May 1913 he set a new altitude record of 11,450 feet, winning a 50 pound prize from the Brooklands Automobile club. In August of the same year, with an Australian co-pilot, he entered a contest run by the Daily Mail to fly a circuit of Britain in a seaplane. Hawker was forced to land only a few miles short of the finish line and for his efforts was awarded a 'special prize' of 1000 pounds by the newspaper. He set a new world record for seaplanes of 1043 miles and flew for 21 hours and 44 minutes. In 1914 Hawker came to Australia and was feted as a hero. He bought with him a Sopwith biplane, the 'Tabloid', which could fly at 90 mph. At Caulfield Racecourse in Melbourne, flights at 20 pounds a head were offered. Such was his fame that Hawker's aircraft was mobbed and the crush made it impossible to take off and land. However, whilst in Australia, he took many noted dignitaries for joy flights, thereby enhancing the reputation of air transport as an effective and safe mode of travel for the future. Upon his return to England in June of 1914, Hawker survived a serious crash, when making a serious and deliberate attempt to recover from a 'spin'. An aircraft would enter a spin when a wing 'stalled' and no pilot had found a way to recover a spinning aircraft. A spin invariably claimed the lives of any pilots who were unfortunate enough to enter into one. A few days later, Hawker became the first pilot to learn how to recover an aircraft from a spin by forcing the aircraft into a dive, which was a counter-intuitive move. By forcing the aircraft into a dive, Hawker was able to increase the airflow over the control surfaces and regain control of the aircraft. His brave and daring research would save the lives of many aviators of the future. In 1919, leaving from Newfoundland with Commander Grieve and flying a single-engine biplane, he crashed into the sea in an attempt to be the first to fly across the Atlantic. Fortunately, he was rescued by a merchant ship which just happened to be passing by. Hawker was presumed lost until the ship docked, as no radio was on board. The London Daily Mail had sponsored a competition for a transatlantic flight, and although Hawker and Grieve failed to complete the ocean crossing, the newspaper awarded them 5000 pounds. Both Hawker and Grieve were awarded the Air Force Cross at Buckingham Palace for their attempt. Inspired by the epic flight, Australian Poet A.B. (Banjo) Patterson penned a poem, titled "Hawker The Standard Bearer" In 1920 Hawker formed the H.G. Hawker Engineering Co. to make two stroke motorcycle engines, but he also turned to designing aircraft and cars. All this eventuated as a result of the British Government's decision to cancel all contracts with Sopwith after World War 1, leaving that company in dire financial straights. Hawker and others bought all Sopwith's patents and formed the new company. On the 12th of July, 1921, at the age of 32, Hawker was killed whilst preparing for the Aerial Derby of 16th July when his aircraft caught fire and crashed. His fearlessness, experience and mechanical knowledge exerted a great and enduring influence on the development of flying in its early days and for all time. On the death of Harry Hawker, King George V wrote that "the nation has lost one of its most distinguished airmen, who by his skill and daring, has contributed so much to the success of British aviation". Another pioneer of aviation, Lord Brabazon of Tara, wrote that Hawker was the "...idealised sportsman of the youth of the country." Moorabin's Airport, in Melbourne, Victoria, is named after Hawker.

|

© Copyright 1999-2003 CTIE - All Rights Reserved - Caution |