John Joseph Montgomery (1858-1911)

by: National Air Museum, Smithsonian Institution,Washington, D. C. John Joseph Montgomery made outstanding contributions to aviation by his early research into the nature of the laws of flight, by building and testing a series of gliders, by developing improved methods of glider control, and by bringing wide-spread attention to aviation by the public demonstrations of his glider. Montgomery was probably the first person in America to be supported freely in the air in a heavier-than-air craft, a glider, without power or control, in 1883. His initial research into the laws of flight was based on a study of birds and tests of models. He is reported to have made and tested his first full-scale glider in 1883 and to have manned it in runs down a long slope in Otay, California. During those runs, on the testimony of his brother James who pulled the launching line, John was lifted from the ground. He continued to design and test gliders, using curved wings, a stabilizing tailplane, and efforts at control by manipulating wires which extended laterally to brace the wings. On April 29, 1905, in the presence of thousands of spectators at Santa Clara College where Montgomery was a professor, one of his gliders, named for the College, and manned by Daniel Maloney was raised by a captive balloon to an elevation of about 4000 feet. There it was released to be skillfully maneuvered during its eight minute descent to earth, and landed without injury at a pre-selected location about three-fourths of a mile from the launching site. Other successful glides followed. At the start of another demonstration on July 18 of that year, the glider, unknown to Maloney, was damaged as it was lifted from the ground. When he separated from the balloon at high altitude, further breakage occurred and Maloney died in the fall. This tragedy suspended Montgomery's efforts until six years later when he designed a glider having a main wing, fixed fin and tailplane, four-wheeled undercarriage, underslung seat, and a spectacle-form of control handle. From a rolling take off at the crest of a hill near Evergreen, California, he made more than fifty glides, following generally the contour of the slope. During his final glide, October 31, 1911, he is reported to have experienced dizziness and made a rough landing, the glider turning partly over. Montgomery's head struck against a protruding bolt causing a brain penetration. He died shortly thereafter. John Joseph Montgomery was a sincere student of flight whose efforts covered his adult span of life dating from his graduation at St. Ignatius College in 1879. Economic necessities and application to other efforts interrupted his aeronautical progress. The widespread publicity resulting from his glider demonstrations in 1905 awakened public attention at an early date to the possibilities of human flight.

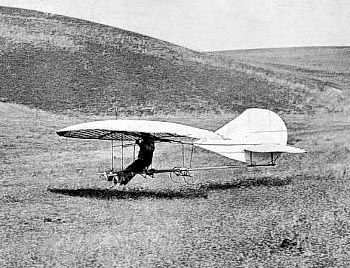

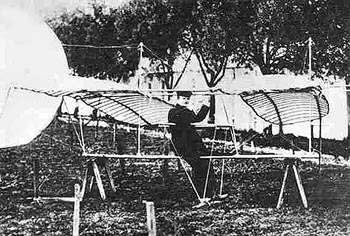

Planeur monoplan du scientifique John J. Montgomery,

John J. Montgomery : 1883 John Montgomery makes world's first "controlled flight" in a "heavier than air" craft, flying 600 feet in a glider at Otay Mesa.

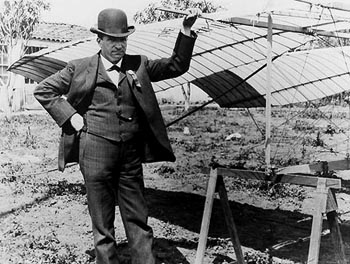

John J. Montgomery, 1905 http://www.sandiegohistory.org

John J. Montgomery Glider (1883) The glider was the first heavier-than-air human-carrying aircraft to achieve controlled piloted flight. On his first successful flight, August 28, 1883, John Montgomery soared at about 600 feet. The Montgomery glider's success demonstrated aerodynamic principles and designs fundamental to the modern aircraft. In 1883, at his family's ranch at Fruitland in Otay Valley, California, John Montgomery (1858 - 1911) observed the natural airfoil shape of birds' wings and incorporated that shape into the development of the Montgomery glider. He designed a parabolic wing section with more curvature toward the front of the wing, giving it a gull-like wing shape and high lift. Montgomery also created the gliders stabilizing and control surfaces at the rear of the fuselage. The first glider flown was destroyed when the rope caught the gull during an 1883 flight and it crashed. A replica was created by Judy and Howard Ace Campbell, who followed John Montgomery's notes, and is on display at the Hiller Aircraft Museum in Redwood City, California until a larger aircraft museum is constructed at the San Carlos Airport. An exception has been made regarding replicas because of the fundamental significance of the Montgomery glider to an industry largely associated with mechanical engineering.

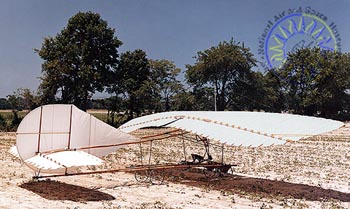

1883 John J. Montgomery Glider (replica) The Western Museum of Flight's 1883 Montgomery Glider is an exact replica of the one designed, built, and flown by John Montgomery in 1883. This aircraft is notable for being the first aircraft incorporating flight controls and a shaped airfoil. On 28 August 1883, John Montgomery was reported to have flown his craft for a distance of 600 feet on its first flight. By moving the control lever for the movable tail surface, he could control its flight to take advantage of wind conditions. The flight occurred at Otay Mesa near San Diego, California. This was the first reported instance of "controlled" flight of a "heavier than air" craft. Over the next 10 years, John Montgomery (who had a Master of Science degree) continued to study the lift effects of various airfoil designs. In 1894, his design and experimental results were published in summary form in Octave Chanute's "Progress in Flying". The Wright Brothers read this book. John Montgomery continued to focus on the stability and control of aircraft using unpowered configurations. He was the first person to use the term "aeroplane" and wrote a booklet with that title. He was granted the first "aeroplane" patent in 1906. In 1910, John Montgomery entered into an agreement with Victor Loughead (later Lockheed) to build a powered aircraft. John Montgomery was to provide the airframe and Loughead the engine. They agreed that John Montgomery would perfect the airframe by building a highwing monoplane with landing gear, a modern-looking yoke control stick, and a bucket-type seat. John Montgomery died on 17 October 1911, after this aircraft crashed on its maiden flight due to a sudden pitchup. His last words were, "How is the machine?" Norman Ward of El Centro, California, reconstructed the 1883 Montgomery Glider and won an award with it in September 1973. This replica was destroyed in the San Diego Aero-Space Museum fire in February 1978. Ward again reconstructed a replica, which was donated to the Western Museum of Flight in April 1985.

John J. Montgomery's Aeroplane : First Heavier than Air, Controllable Flight John Joseph Montgomery was the first American to build a glider that flew. He was also the first to achieve practical control of his craft in the air. He began his experiments in 1883, and, by 1905, was giving public demonstrations in and around the Santa Clara Valley. Montgomery studied and tested his aeroplanes in between college teaching assignments in Northern California. He earned his Ph.D. from Santa Clara College in 1901.

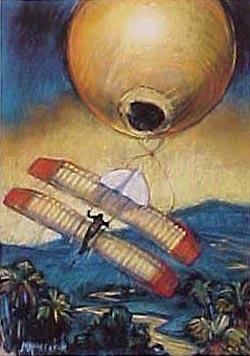

John J. Montgomery : Flight over Evergreen Valley by Mary Ann Henderson

Montgomery used hot-air balloons to lift his glider into the air. After being released from the balloon, the "aeroplane" could be piloted to Earth. A circus daredevil that parachuted from balloons, Daniel John Maloney, approached him, saying, "I will have a balloon hoist me in your aeroplane to the four-thousand foot level, then I'll cut it loose and glide to the ground." Maloney's first flight, a twenty-minute graceful descent, was a delight to behold. Montgomery's most spectacular demonstration was when his monoplane glider, Santa Clara, was cut loose from a balloon several thousand feet in the air and flew 8 miles (13 km) in 1905. Montgomery Hill in the Evergreen Valley is named after him and is the place where in 1911, after a crash landing, he met his end cradled in the arms of his bride. A special thanks goes to E. Charles Vivian and his History of Aeronautics and Theodore W. Fuller for his San Diego Originals. Mary Ann Henderson

Mary Ann paints in both oil and pastel, finding pastel to be particularly exciting because it is, basically, a drawing medium and drawing is her passion. The direct and immediate application of pigment to paper gives her a real sense of power and control. She can manipulate line, form, and color without making accommodations to the "chemistry" of the medium that must be considered when working with watercolor or oils.

John J. Montgomery's "Evergreen" John Joseph Montgomery was one of the earliest aeronautical experimenters in the United States. Born in 1858, he exhibited a boyhood interest in flight, making several aircraft models. He began serious work in aeronautics in 1881-82, developing models with flat wing surfaces. After these proved unsatisfactory, he patterned the lifting surfaces of his models after the curved wings of birds. In the 1884-1886, he built three full-sized gliders. The most significant was a monoplane glider spanning slightly more than 6 m (20 ft), and with it he made a glide between 100-200 m (325-650 ft) at Otay Mesa, California, in the summer of 1884. The glider had little means of control and was not flown again. At this time, Montgomery was working in isolation. Whatever merits his 1884 glider had, they were not disseminated among the aeronautical community until 1894, when Octave Chanute mentioned it in his compendium of flight research up to that time, Progress in Flying Machines. But even that account was very brief.

John Montgomery's "Evergreen" today Download a 750pixel image

In the late 1890s and the first years of the twentieth century, Montgomery began experimenting with tandem-wing gliders. The first ones were small, unpiloted craft, typically flown tethered on a line between posts. Between 1904 and 1906, he built 3, possibly 4, larger tandem-winged gliders intended to carry a pilot, spanning 6-7 m (20-24 ft). The first was built and tested in 1904, again tethered to posts, with Montgomery on board. A slightly larger version followed, which was carried aloft suspended beneath a balloon, and then released to glide back to the ground. Montgomery enlisted Daniel John Maloney, a balloonist and parachutist, as his pilot. In 1905, they gained great attention with this glider, named the Santa Clara, after a series of public demonstrations in the spring and summer of that year. Maloney made several impressive glides on March 16, 17, and 20 in Santa Cruz, California. Then, on April 29, they made their first major public demonstration of the Santa Clara. Before 1,500 people, at Santa Clara College, Maloney ascended to an altitude of 1,200 m (3,900 ft) suspended from the balloon. After cutting the suspension rope he descended safely to the ground, much to the amazement and delight of the crowd. The next major demonstration was scheduled for May 21 at the Alameda Race Track in San Jose, California. To raise funds for further aeronautical research and experimentation, admission to the event was charged. As before, Maloney began his ascent in the Santa Clara by balloon, but on this occasion the suspension rope snapped at an altitude of 45-60 m (150-200 ft). He managed to reach the ground safely, but the spectators, expecting more, were disappointed and booed Montgomery and Maloney. A second attempt was made with a back-up glider, similar to the Santa Clara, called the California. Once aloft, problems arose with the balloon and the glider and, in the interest of safety, Maloney simply descended with balloon and glider still connected, landing 50 km (31 mi) away. The failures were humiliating after the triumph of April 29. On July 18, 1905, Montgomery and Maloney were back at Santa Clara College for another attempt to fly the Santa Clara. Again a problem occurred, but this time Maloney was not so fortunate. As the balloon was released, one of its handling lines, unnoticed by Maloney, was caught up in the structure of the Santa Clara above the wings. Montgomery saw the mishap and called to his unsuspecting pilot to just ride down with the balloon. Maloney failed to hear him and ascended to 1,200 m (3,900 ft). After cutting the suspension rope as normal, the errant handling line damaged the glider. Maloney struggled unsuccessfully to gain control of the crippled craft and crashed to his death. Undeterred by the mishap, Montgomery resumed his experiments late in 1905 and early 1906. He returned to the earlier method of flight testing his gliders tethered to posts arranged on a hillside. On February 22, 1906, however, another balloon ascension with a suspended glider was made, presumably with the repaired Santa Clara or the California, or possibly some other glider. The pilot, David Wilkie, lost control of the glider as it separated from the balloon at 600 m (2,000 ft), only regaining equilibrium at 90 m (300 ft) when he could hear Montgomery shouting instructions from the ground. The glider was slightly damaged upon landing. Wilkie convinced Montgomery to let him make a second try a few days later, but the balloon was damaged during inflation so no flight could be attempted. Montgomery then decided not to allow Wilkie another balloon-assisted flight trial. The great San Francisco earthquake of 1906 ended Montgomery's aeronautical work for several years, but he resumed his efforts in 1911 with a new glider called the Evergreen. Moving away from his basic tandem-winged design of the pre-1906 period, the Evergreen was a monoplane glider with a conventional tail with the pilot seated below the wing. Montgomery flew the Evergreen himself. Between October 17-31, 1911, in the Evergreen Valley, just south of San Jose, he made more than 50 glides with his new aircraft, each approximately 240 m (785 ft). On October 31, after making an adjustment to the angle of the horizontal stabilizer, he was airborne once again. Flying at an altitude of less than 6 m (20 ft), the Evergreen stalled, sideslipped, came down on the right wingtip, and turn over. Montgomery hit his head on an exposed bolt and died from his injury two hours later. After his death, the remains of Montgomery's gliders were given to the University of Santa Clara. In 1947, the Smithsonian Institution acquired from the university parts of the Evergreen and what was believed to be a wing panel from the Santa Clara. In 1979-80 the Evergreen was restored. At that time, the university sent some further original parts of the Evergreen that were not included in the original Smithsonian acquisition in 1947. This enabled the restored aircraft to be 80-85 percent original. The museum also has, from the 1947 acquisition, one wing panel from one of the tandem-winged Montgomery gliders of 1904-05. Initially believed to be from the Santa Clara, in which Maloney was killed in 1905, it is shorter in span, has many fewer ribs than the Santa Clara wing, and is therefore almost certainly from the slightly smaller, earlier tandem-winged first prototype. It is preserved in its original condition.

Engines of our Ingenuity : No. 432: John J. Montgomery Today, a fable about the long road from a dream to reality. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them. John Montgomery graduated in science from Santa Clara College in 1880. California was still a frontier. But in that sleepy land, 20th-century America was exploding into being. Montgomery dreamt of flying. So he went back to his family ranch near San Diego to make an airplane. First he made two flapping-wing ornithopters. They failed, but he did better with his next try. He made a fixed-wing glider and hauled it up a hill. Facing a gentle breeze, he took a small hop and was airborne. He skimmed downhill for a hundred feet or so. On the second flight he crashed and wrecked the glider. He built two more gliders. The first one -- the one that flew -- had wings with cambered airfoils, like the wings that would carry the Wright Brothers into the sky twenty years later. Next, he gave up cambered airfoils, but he added a control surface that would respond to gusts. That one didn't fly. He put the airfoils back on the third glider but gave up the control surfaces. That one didn't fly either. We heard no more from Montgomery until 1893. He was secretive about what he'd done. Then Octave Chanute organized a conference on flight in Chicago. Montgomery showed up to tell Chanute that he was the one American who'd really flown. I've just told Montgomery's story as Chanute repeated it in his conference report. Montgomery read Chanute's proofs, and he okayed them. But when the Wrights and others succeeded, Montgomery began to chafe. In 1909 he wrote his own book on flight. He began revising history. His old flight expanded from 100 to 600 feet. He claimed other flights as well. He also found a champion named Victor Loughead. Loughead wrote two books about flight and kept adding to Montgomery's legend. He was, according to Victor Loughead, one of the great mathematical thinkers of all time and the inventor of airplane controls. By the time Loughead was done, Hollywood had made a movie about Montgomery. The wake of the Wright Brothers is full of stories like this -- full of might-have-beens. But Victor Loughead had two young half-brothers -- Allen and Malcom. They were also bitten by the bug of flight. And they were doers, not storytellers. In 1912 they made a neat little seaplane that really flew. They also changed the old Scottish spelling of their name. They changed it from Loughead to Lockheed. And their Lockheed Company has been making great airplanes ever since. Victor Loughead's younger brothers finally gave Montgomery's frustrated, overblown dream its earthly home.

John J. Montgomery Born 1858 at Yuba City CA. Died Oct 31, 1911, near San Diego CA. John Joseph Montgomery's family moved to Oakland in 1863 when he was five years old. As a toddler he liked to lie on a pillow and "pretend to fly," his mother said. He watched birds, and he studied clouds, wondering if he could somehow fly by catching one. He flew kites of all shapes and sizes, and drafted his brother, James, to help in crude flight experiments. At age 11 he joined a Fourth of July crowd to see Frank Merriott pilot a steam-propelled hydrogen balloon, then returned home to build a model of the craft. He attended Santa Clara University when it was still a college, then transferred to St Ignatius College in San Francisco to a Masters of Science degree. In 1883 he moved with his family to a ranch near San Diego. His father, Zachary Montgomery, distinguished as a lawyer, journalist, and politician, took up farming and publishing a weekly newspaper. Young Montgomery, as foreman of the farm, wasted no time in setting up a workshop in the barn, complete with a lathe. His sister, Jane, pumped the bellows on a steam boiler for heat to help shape ash strips into parabolic, cambered wing ribs resembling wings of birds he had studied. One August day in 1883, to the edge of a mesa on the ranch he and James carried the parts and assembled a glider with wings shaped like a those of a gull's. The brothers waited until the breezes picked up, then James tied a rope to the front of the craft and waited down the slope until John's signal. He pulled the rope and ran a few steps until the glider rose. At a height of about 15', Montgomery soared 600' to a graceful landing. It was the world's first controlled heavier-than-air flight, and it preceded Orville Wright's engine-driven flight by 20 years. "[We took my] apparatus to the top of a hill facing a gentle wind," he later described the event.

"There was a little run and a jump, and I found myself launched in the air. A peculiar sensation came over me. The first feeling in placing myself at the mercy of the wind was that of fear. Immediately after came a feeling of security when I realized the solid support given by the wing surface. And that support was of a very peculiar nature. There was a cushiony softness about it, yet it was firm. When I found the machine would follow any movement in the seat for balancing, I felt I was self-buoyant..."Montgomery's feat and subsequent flights did receive some mention by the local press, and later experiments in the 1890s around Santa Clara were publicized, but for years he was largely unrecognized as an aviation pioneer. Even today many aviation history books still ignore him, even though a 1946 feature film, "Gallant Journey," dramatized his story, as did a 1967 biography by Arthur D Spearman, John J Montgomery: Father of Basic Flying. He continued to study and test his theories of flight between college teaching assignments in Northern California and earning a PhD from Santa Clara College in 1901. One day a circus daredevil, Daniel John Maloney, who parachuted from balloons, approached him with a plan. "I will have a balloon hoist me in your aeroplane to the 4000' level, then I'll cut it loose and glide to the ground." Maloney's first flight was a 20-minute graceful descent, but a second attempt, in 1905, proved fatal when a dangling balloon release cable tangled above him and caused the glider to crash. During this period as a mathematics teacher at St Joseph's College, he built a wind-tunnel to experiment with wing shapes and flight controls, patented his "Improvement in Aeroplanes" in 1906, and in 1909 even built an electric typewriter and patented an alternating-current rectifier, which he sold to a San Francisco company and invested the money in aircraft designs. During two weeks in October 1911, Montgomery had made 55 successful flights at a camp at Evergreen, near San Jose. Despite a doctor's advice that, at 53, he should stay on the ground, Montgomery wanted to make one more test flight to evaluate some changes made in his latest craft. It was a fateful decision, for soon after he became airborne, the plane stalled, slipped off on a wing, and crashed. A protruding stove-bolt penetrated his brain behind an ear, and he died before a doctor could reach the scene. John J Montgomery's findings and airplane designs have earned him a well-deserved place with Octave Chanute and Samuel Pierpont Langley as American pioneers in controlled flight before the Wright brothers accomplished their Kitty Hawk milestone. (- Adapted from San Diego Originalsby Theodore W Fuller (California Profiles Publications 1987))

John J. Montgomery's Aeroplane : First Heavier than Air, Controllable Flight John Joseph Montgomery was the first American to build a glider that flew. He was also the first to achieve practical control of his craft in the air. He began his experiments in 1883, and by 1905, was giving public demonstrations in and around the Santa Clara Valley. Montgomery studied and tested his aeroplanes in between college teaching assignments in Northern California. He earned his Ph.D. from Santa Clara College in 1901.

American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics : The Gliders of John J. Montgomery On August 28, 1883, at Otay Mesa near San Diego, California, a manned glider left the surface of the Earth and soared in a stable, controlled flight. At the controls was John Joseph Montgomery, age 25, who had designed and built the fragile craft. After the launching, John and his brother James, who had helped launch the glider, paced off the distance of the flight as 600 feet. The 1883 flight of Montgomery's glider was the first manned, controlled flight of a heavier-than-air machine in history. In 1896 Montgomery, a professor at Santa Clara College (now University), worked on a series of model gliders which would eventually lead to the 1905 "Santa Clara." In a historic flight at Santa Clara College, the "Santa Clara" performed several horizontal figure eights, well- controlled turns, and spirals after being dropped from 4,000 feet by a balloon. In 1911, Montgomery designed a new glider, the "Evergreen", which had a modern design and several ingenious elements which set it apart from its contemporaries. About the Speaker: Dr. Ardema has been professor and chairman of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at Santa Clara University for the past 10 years. For the Prior 21 years he was at NASA-Ames Research Center in a variety of research and management positions. From 1980-82 he was the Research Assistant to the Ames Director. Dr. Ardema received his B.S., M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in mechanical engineering from the University of California at Berkeley. Dr. Ardema is an Associate Fellow of the AIAA and has over 120 research publications in the areas of optimal control, differential games, singular perturbations, flight path optimization, structural analysis, and aircraft preliminary design and performance.

John Joseph Montgomery

Montgomery seated at the controls of his 1903-1904 bamboo longeron tandem-wing model University of Santa Clara Archives

If asked to name pioneers in aviation, most people respond with the Wright Brothers. But there are others whose research in aero-dynamics set the stage for the Wrights' success. Such men as Chanute, Langley, Lilienthal, and Montgomery played significant roles in developing the knowledge required for ultimate mastery of human flight. The contributions of John J. Montgomery are not fully recognized, but such scientific greats as Alexander Graham Bell gave him the accolade he deserves: "All subsequent attempts in aviation must begin with the Montgomery machine." John Montgomery* was a native Californian, born in 1858 in Yuba City. His father Zachariah Montgomery was a lawyer, public servant and journalist. His mother Ellen Evoy Montgomery was the daughter of the celebrated Temescal pioneer Bridget Shannon Evoy "probably the only woman who led a covered wagon train across the plains in 1849-1850." Montgomery began his primary education at Notre Dame Academy in Marysville, finishing his secondary education at St. Joseph's Academy in Oakland. He attended Santa Clara College for a year before transferring to St. Ignatius College in San Francisco, where he received a B.S. degree in 1879 and an M.S. degree in 1880. Montgomery's interest in flying began as a boy, when he became intrigued by cloud movement and the flight of birds. His keen mind and excellent education enabled him to develop this interest into a life of scientific research, dedicated to a full understanding of the laws of aerodynamics and their application. In 1882 he joined his family at their farm near Fruitland in San Diego County, where he soon preempted space in the barn for a laboratory. The following year marked a milestone in aviation history - John Montgomery made man's first controlled flight in a heavier-than-air craft. In a letter to his sister, dated December23, 1885, Montgomery wrote of his work:

My attention is still fixed on my flying machine, and I am getting along fast enough to suit myself. Since I last wrote you, I have performed hundreds of experiments and discovered some important facts and laws. I have had many failures and discouragements, but have become convinced more than ever of the correctness of my ideas and plans.Continued research led to a paper which he read to the Aeronautical Conference at Chicago in early August, 1893. The original of that paper, containing the first statements of the principles basic to all flying, is now in the Smithsonian Institution. Returning from Chicago, Montgomery joined the faculty of Mount St. Joseph's College at Rohnerville, where he taught mathematics and science while continuing studies of air- and water-current impacts on edged surfaces, parabolic and plane. From St. Joseph's he wrote his sister on August 30, 1894:

Well, now for science! Some of my work is beginning to tell. A work on flying has been published and my experiments have been described; and three (men) have been mentioned as giving the most reliable data, viz: Maxim, Lilienthal and Montgomery. The author (Octave Chanute) has been writing to me for further notes on my work.Spearman believes Montgomery constructed two small airplanes at Rohnerville - The Pink Maiden, a tandem-wing model with a three-foot-six-inch wingspread and The Buzzard, a four-foot wing-spread model. Certainly the wind currents rising up the Eel River to sweep the bluff where the college stood were ample for observation and experimentation. Upon his return from St. Joseph's, Montgomery tested these models at the Leonard Ranch near Aptos on Monterey Bay by flying them from a trestle. Montgomery's sister recalled that he weighted The Pink Maiden, then "turned it up-side down, and started it from a height ... He said that in ten feet it righted itself, just as a cat will fall on its feet." Montgomery was mastering techniques for insuring stability in his experimental models. The exact dates of Montgomery's affiliation with St. Joseph's are uncertain. His sister reported in later years that upon his return from Chicago in 1893, he left to teach at Rohnerville. Reference to "my return" in his letter of August 30, 1894, indicates he had taken some vacation at the close of the spring term in 1894, but was back for the 1894-95 school year at the school. Other reports from the Leonard family indicate he tested his Pink Maiden and Buzzard models on their ranch in the summer of 1896, after his return from Rohnerville. If he developed these models the previous year, it appears he taught at St. Joseph's during the spring of 1894 and academic years 1894-95, and 1895-96, but there is no documentation of this.

Photograph taken before Montgomery's April 29,1905 flight at Santa Clara. From left to right: Association Justice W. G. Lorigan, Frank Hamilton (owner of the hot-air balloon), J. J. Montgomery, and aeronaut Dan Maloney. University of Santa Clara Archives

Returning to Santa Clara College, Montgomery began experimenting with larger, weighted models which were trigger-released from cables stretched across a small canyon. He built wind tunnels to study parabolic wing curve and length, and rudder and rear-stabilizer control. His intensive research culminated on April 29, 1905. A hot-air balloon lifted aeronaut Daniel J. Maloney 4,000 feet astride the aeroplane Santa Clara. Cutting himself loose, Maloney gracefully maneuvered the glider for 15-20 minutes, alighting gently on his feet at a target near the Santa Clara campus. The correspondent to the Scientific American wrote in the May 20, 1905 issue: "An aeroplane has been constructed that in all circumstances will retain its equilibrium and is subject in its gliding flight to the control and guidance of an operator." On October 31, 1911, after two weeks of successful flights, Montgomery was killed when his craft turned abruptly, throwing his head against a protruding stove bolt. The world lost a dedicated scientist who lives today in the annuals of aviation history as the father of basic flying. In the February 24, 1946 Humboldt Times, Will Speegle wrote:

While at St. Joseph's he experimented earnestly in the creation of flying machines... Many times I have talked with the late Senator John F. Quinn who was a student at the Academy and he assured me that Montgomery made considerable progress in his plane while in this county. Fred Houck, who was also a student there, remembers well how Montgomery carried on his experimentsInformation from John Joseph Montgomery: Father of Basic Flying by Arthur D. Spearman, S. J. University of Santa Clara, 1967.

Further Reading

John J. Montgomery, 1883 Glider Cached copy : h189.pdf Spearman, Arthur D., John Joseph Montgomery: Father of Basic Flying, University of Santa Clara, 1967.

|

© Copyright 1999-2006 CTIE - All Rights Reserved - Caution |

John Joseph Montgomery, 1858-1911

John Joseph Montgomery, 1858-1911